Presently just five US tech companies account for nearly 25% of the S&P 500 market cap. We discuss resurgence of big US tech and what it means for investors.

Hello and welcome to Reflections on Investing with the Cornell Capital Group.

This is Shaun Cornell, and I'm joined by Professor Bradford Cornell and Andrew Cornell. Today, we want to talk a little bit about market concentration.

It's something we mentioned in our most recent quarterly memo back in April, where we noticed that the market was becoming dominated by just a handful of stocks. And that trend has continued. Now, we find the market is even more concentrated.

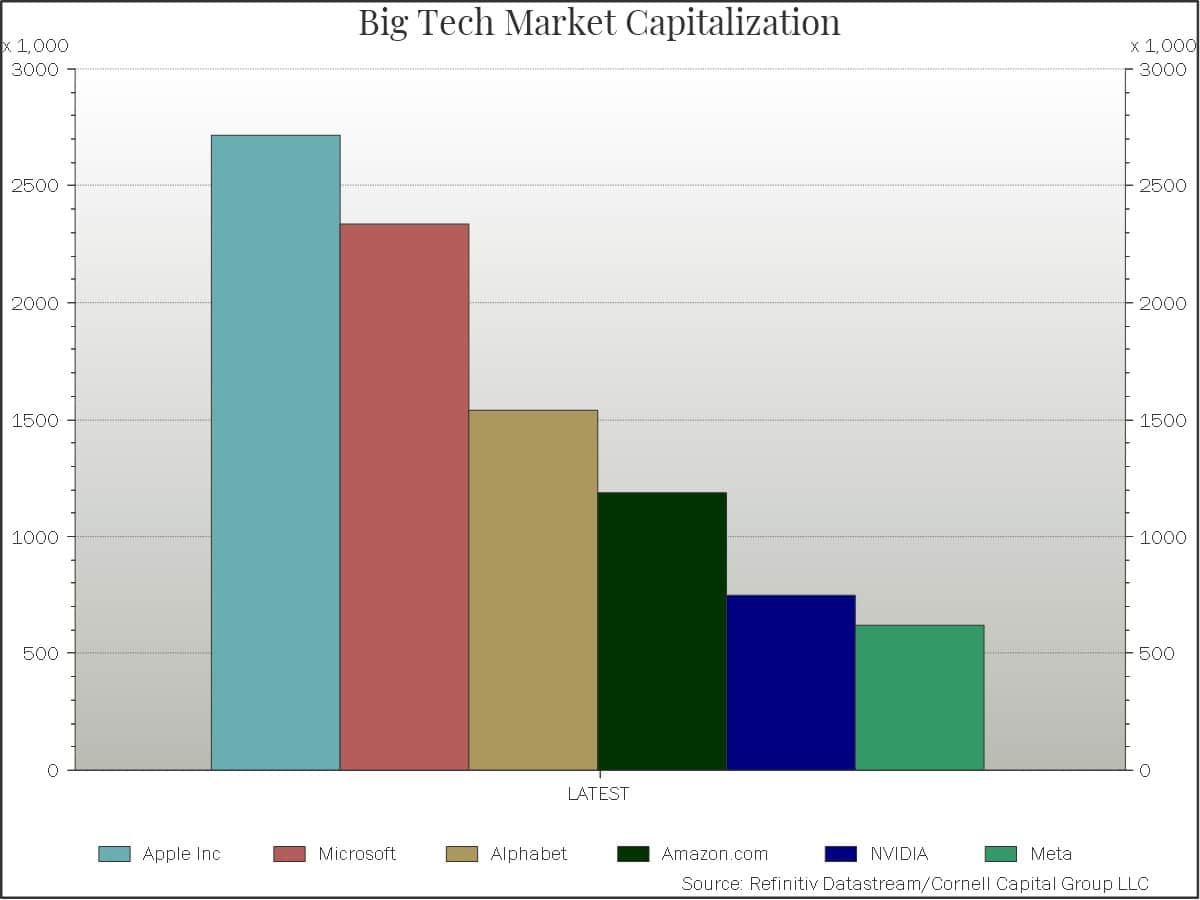

Let me show you the stocks we're talking about here. They're all large U.S. tech firms, so we have Apple leading off, which has a market cap of around 2.7 trillion dollars. That actually eclipses the entire UK stock market right now.

And then Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, and Meta, which I'm sure you're all familiar with.

In fact, Shaun, if you add them up, you're looking at almost nine trillion dollars in six companies, which is quite remarkable to say the least.

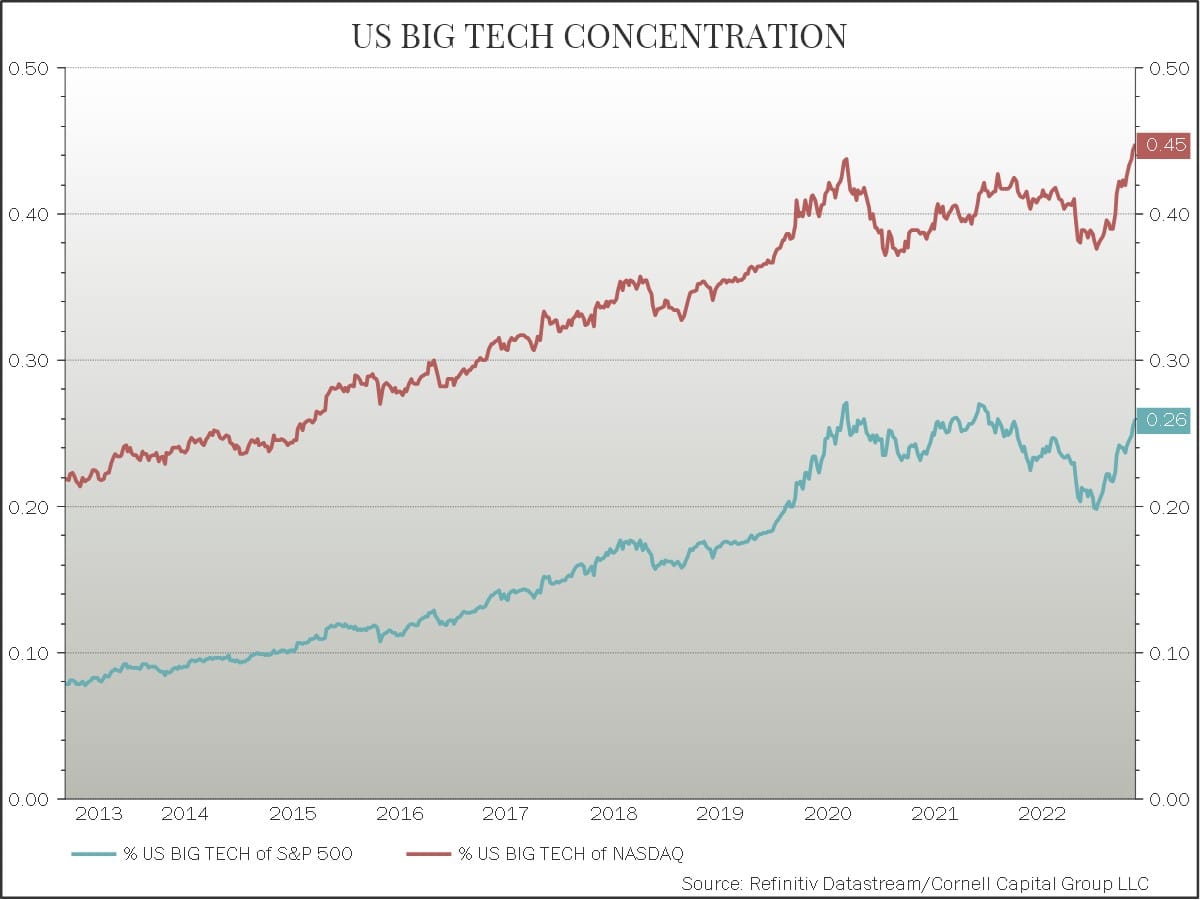

So, in this next chart, we can see the concentration—the fraction of these six companies in total—as a percentage of the S&P 500 in the blue and the percentage of the NASDAQ index in red. And this is over the last 10 years.

You can see it's been trending up, but especially over the last few months, we've seen a sharp, dramatic increase in this concentration.

So, what would you say is the implication here? I mean, you've noticed this trend, so what does that mean? Is that a problem?

That's a good question, Drew. I mean, it could be, because if there were something that threatened these companies, it could have a dramatic effect on the entire market.

It's also concerning that all of these companies are in the same sector—they're all technology companies. And furthermore, if you're a passive investor, and you're just investing in the S&P 500, you know, you might be a lot less diversified than you may think.

Well, when we look at this, Shaun, and we see that they account for 26% of the S&P and almost 50% of the NASDAQ, you said, "Well, these are remarkable companies. These are wonderful companies. They make great products that they have impressive barriers to entry in some cases. Why shouldn't they be valuable?"

Well, that's all true, but the question is, how valuable? Remember, investing amounts to comparing price and value. And at some point, no matter how good the company is, the price may exceed its value.

And given how important these companies have become, there's a threat that we may be entering that space, and we can talk more about that in a minute when we look at the upcoming slides.

This is kind of another way to look at it. This is a chart over the last three months, kind of when we started seeing that sharp increase in the level of concentration. But we have in the blue the S&P 500, and the S&P 500 to review is a market cap weighted index, so these big companies like your Apples and Microsofts are going to be more heavily weighted. And then versus this is the S&P 500 if you just weight every company equally.

And we can see there's been a pretty big divergence, where the S&P 500, which has more weight for these bigger companies, is significantly outperforming the equal weighted version.

In fact, the equal weighted version is actually down over the period, even though the index is up. So, the big boys have been pulling up the index while the little guys have actually been falling.

Yeah, and again, it's your point about you know, these being remarkable companies. They are, but there's at a certain price which still can be too high. You know, they're not infallible. They're not immune to competition.

Another thing you can take away from this chart is that it's not consistent with the so-called small firm effect, in which there's been much research in academia showing that firms with small market capitalizations tend to have higher returns than those with big market capitalizations.

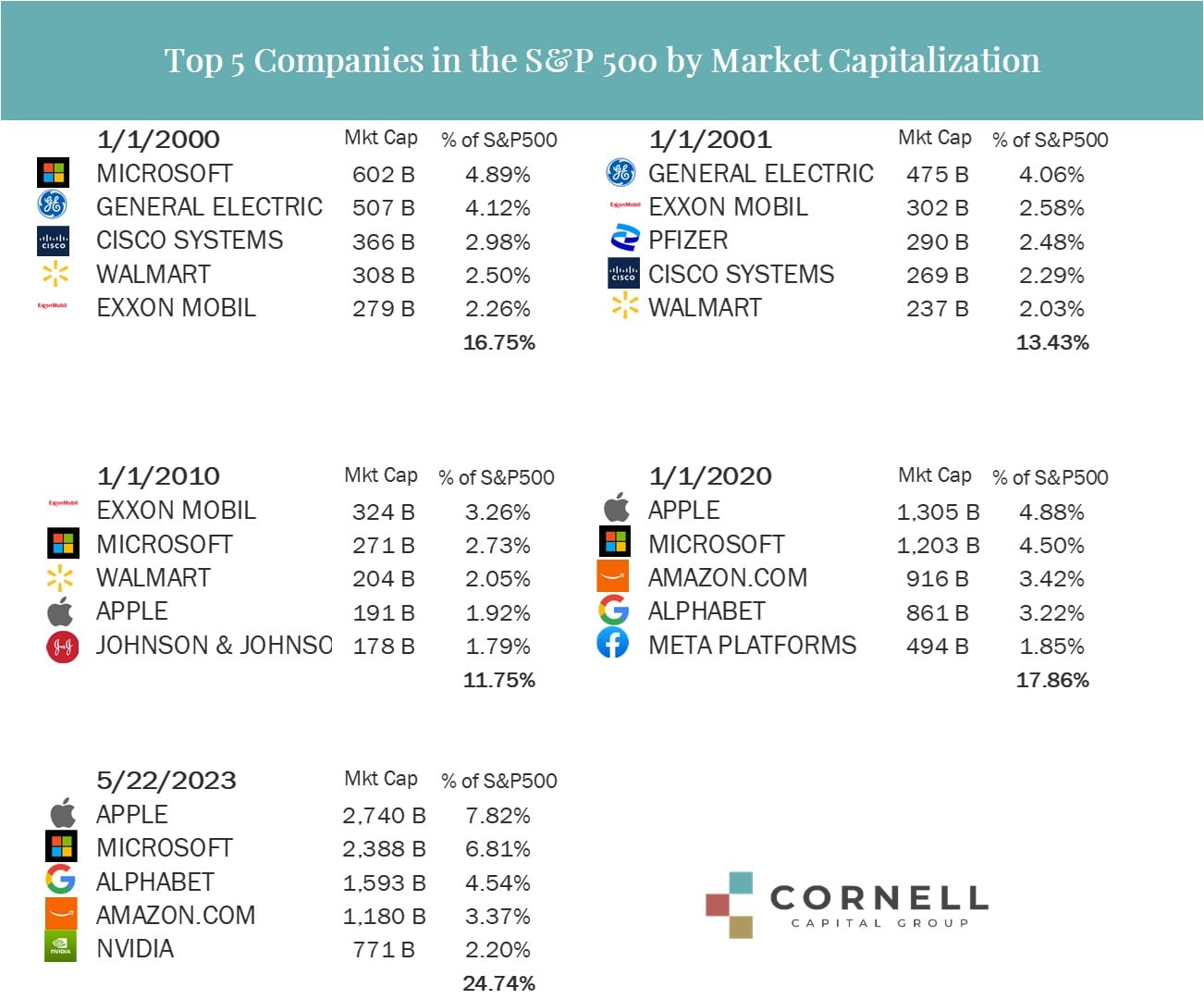

While that may have been true some time ago, it hasn't been true in recent years, and it's clearly not true in this short time period. A good point. So, this is actually a chart from our quarterly memo, which we updated, which shows just the top five companies in the S&P 500 by their market capitalization over a few key years.

We started off in the tech bubble at the beginning of 2000, then in 2001 after that had started to deflate, again in 2010, then 2020, and now the current. When you look at this, one thing that grabs you immediately is the dramatic differences between January 1, 2010, and the current day.

First, the companies are different. Only Apple and Microsoft make it into both lists. Second, the top company in 2010 was Exxon Mobil with a $324 billion market cap and a 3.26% weight. Jump forward to the current day, and Apple has a market cap of $2.74 trillion, which is over eight times as much as Exxon had in 2010. Apple's weight has more than doubled, and the weight of the top five has well more than doubled. So we're looking at a very different market than we saw as recently as 2010.

If you look at the market at the height of the bubble in 2000, Microsoft was the most valuable company. To some extent, the speculators were right that Microsoft would become one of the most valuable companies in the world again in 2022. But you're just looking at two points in time. In fact, if you bought Microsoft on January 1, 2000, your return would be zero for roughly 17 years. And if you bought Cisco, you're still down to this day. Cisco never achieved the same return or got any higher than it did in early 2000.

Looking at the present day, we see that Nvidia was down more than 70% just recently and has come all the way back to its November 21 high. So there's still a lot of volatility and uncertainty among these high market cap companies.

And it's not just true of the S&P 500, which we're looking at here. Research Affiliates looks at this on a global basis, and they found that the top 10 companies in the world changed dramatically from 1980 to 2021.

You notice these monstrous changes, not only in the individual companies, but in the nature of the industries. 1980 was traditional companies like IBM and AT&T, and particularly oil companies. Eastman Kodak, bankrupt now, was the leading tech company. In 1990, it’s Japan. In 2000, American tech companies pops on including Cisco which Drew talked about and it’s not back to the level yet. In 2010 we see China appeared and became a dominant player and now in 2023 and 2021, suddenly it’s American tech.

So how can we be convinced that if we bought big American tech today, it wouldn't look a lot different in 2030? That's a good question. All of these companies are American companies too. We've seen things change dramatically in the past. In the 1990s, all of the top companies were Japanese. And the Japanese stock market has not gotten back to the level it was back in 1990, over 33 years ago.

It's hard to imagine when you're in the middle of it, but things could change. All of these companies, even Apple and Microsoft, are fantastic huge companies, but they're not immune to competition. They're also seeing developments in China. Who knows what the future will look like in 2030? But these companies all seem to be priced like they will continue to be dominant not just now, but well into the future.

At Cornell Capital Group, we have long-term 70-year discounted cash flow models. To justify the current price of, let's say, Apple, the company has to be dominant not just now or not just through 2030, but beyond 2050. And when we look at this chart from Research Affiliates or we look at our previous chart, these 30-40 year periods of dominance do seem to be the exception rather than the rule.

That makes you concerned, if you were an investor in these companies, that if they do start to lose this dominant position, valuation could drop substantially.

That's exactly why we stress long-term fundamental valuation models in assessing investments and making investment decisions. Companies that are as big and valuable as Apple or Microsoft often move with current earnings announcements. To us, that seems quite silly. It's not the current earnings that give you multi-trillion dollar valuations. It's the ability to maintain those earnings for decades that's the critical question.